Written by: Lana Mason, Archivist

Published: 12/14/2022

Over the course of the 20th century, the disability rights movement in the United States helped to advance cultural awareness, understanding, and support of people with disabilities.[1] By the 1970s, organizations throughout the country, including performing arts theatres like The National Theatre, began to commit to providing more equitable access to their public spaces, services, and experiences.

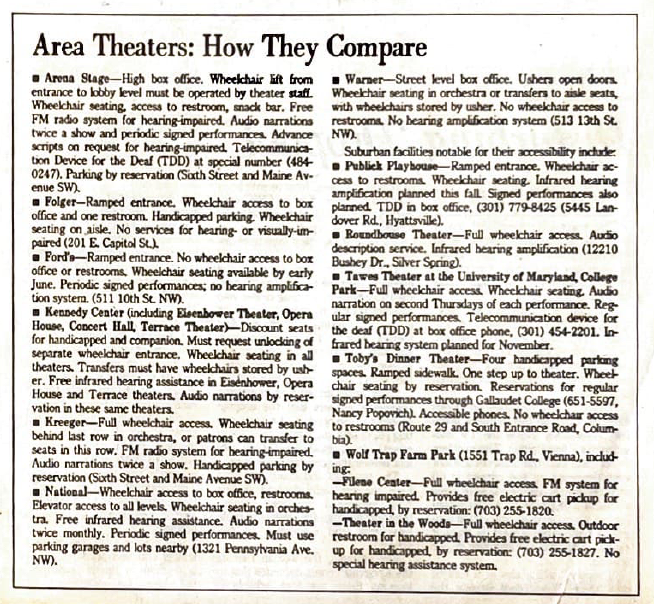

A 1985 Washington Post article analyzed the accessibility of local performing arts theatres and noted that “structural barriers and adverse practices” in some D.C. theatres prevented patrons with disabilities and their companions from enjoying a full, positive experience at shows.[2] Structural barriers included limited physical access to the venue, lack of assistive access to both visual and auditory elements of shows, and dismissive, disrespectful, and negligent attitudes and practices of theatre staff. The National, who had begun to critically evaluate and improve its inclusivity beginning in about 1980, was an early adopter of robust accessibility practices among local theatres.

Spaces

Theatregoers must be able to fully access all public spaces in a venue, including the box office, restrooms, concessions, and seating. The National Theatre had long had basic accessibility structures in place such as a flat, ground-level entrance and elevator access. However, the theatre’s seating itself was not historically accommodating for patrons who used assistive mobility devices. In 1980, supported by members of the theatre’s Disabled Advisory Council, The National installed removable seats in the theatre’s orchestra seating. These seats allowed patrons to remain seated in their wheelchairs and to keep their mobility aids nearby rather than their aids taken away by ushers during the show, which was a common practice in inaccessible theatres.

Sounds

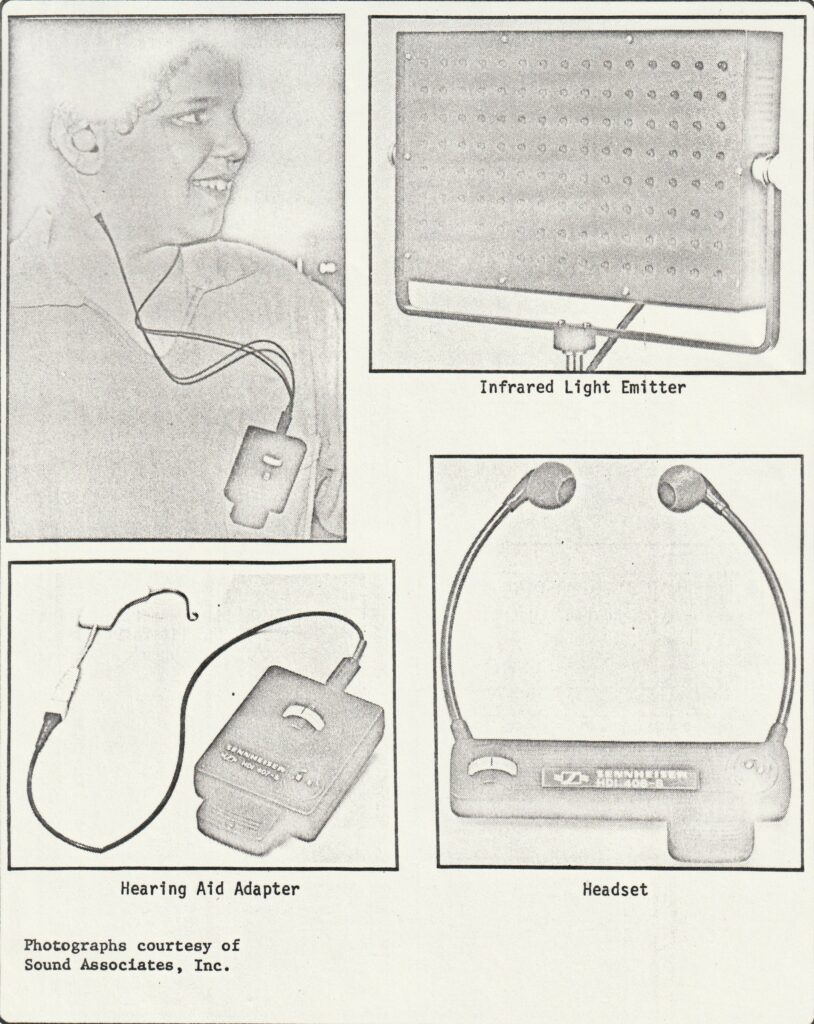

In 1981, The National examined ways to provide a more inclusive experience for patrons who were hard of hearing. The theatre decided to implement a two-part infrared assistive listening system. This system functioned by converting signals from the theatre’s master sound system into infrared light. The light was then transmitted to personal listening devices given to patrons. This allowed for audience members to receive a show’s dialogue, music, and other sounds directly in their ears or hearing aid. The system was first tested at the theatre during the March-May 1981 run of Children of a Lesser God, a play about a deaf woman. The production team owned an assistive listening system which travelled with them on tour. The show’s run at The National gave the theatre an exciting opportunity to see how its audience would receive the system.

Patrons who used the system on the show’s opening night had such a positive experience that The National immediately began raising funds to install a permanent system of its own. The Washington Area Group for the Hard of Hearing supported the fundraising drive, and individuals, foundations, and corporations all contributed. By July 1981, a permanent listening system was installed at the theatre. The National made its listening system even more accessible by making it both free to use and available at all shows.

In the early 1980s, The National also began offering American Sign Language interpretation at select performances of both touring productions and the theatre’s free programming. Interpreters provided deaf and hard of hearing patrons with live translations of auditory information including dialogue and music. In 2022, The National also installed a GalaPro closed captioning software system. Patrons can use this system, either with an app on their personal smartphone or with a loaner tablet, to access closed captions during a show.

Sights

After securing its permanent assistive listening system, The National then looked to improve accessibility for its blind and vision impaired patrons. The same infrared system used for assistive listening could be used to convey audio descriptions of the visual elements of a show. In 1984, the theatre began collaborating with The Washington Ear (now known as the Metropolitan Washington Ear), a non-profit reading service, to provide audio descriptions for productions. The program and intermission audio descriptions were prerecorded so patrons could listen at their convenience. These descriptions typically included a reading of the show’s program text, as well as descriptions of the sets and costumes. During the show itself, an in-person narrator would provide live description of the on-stage activities. The National Theatre was identified in a 1986 article in the Wyoming State Tribune as “the only theater in the country that has a permanent booth near the mezzanine where the narrator sits and describes the show scene by scene as the action happens.”[3]

Attitudes

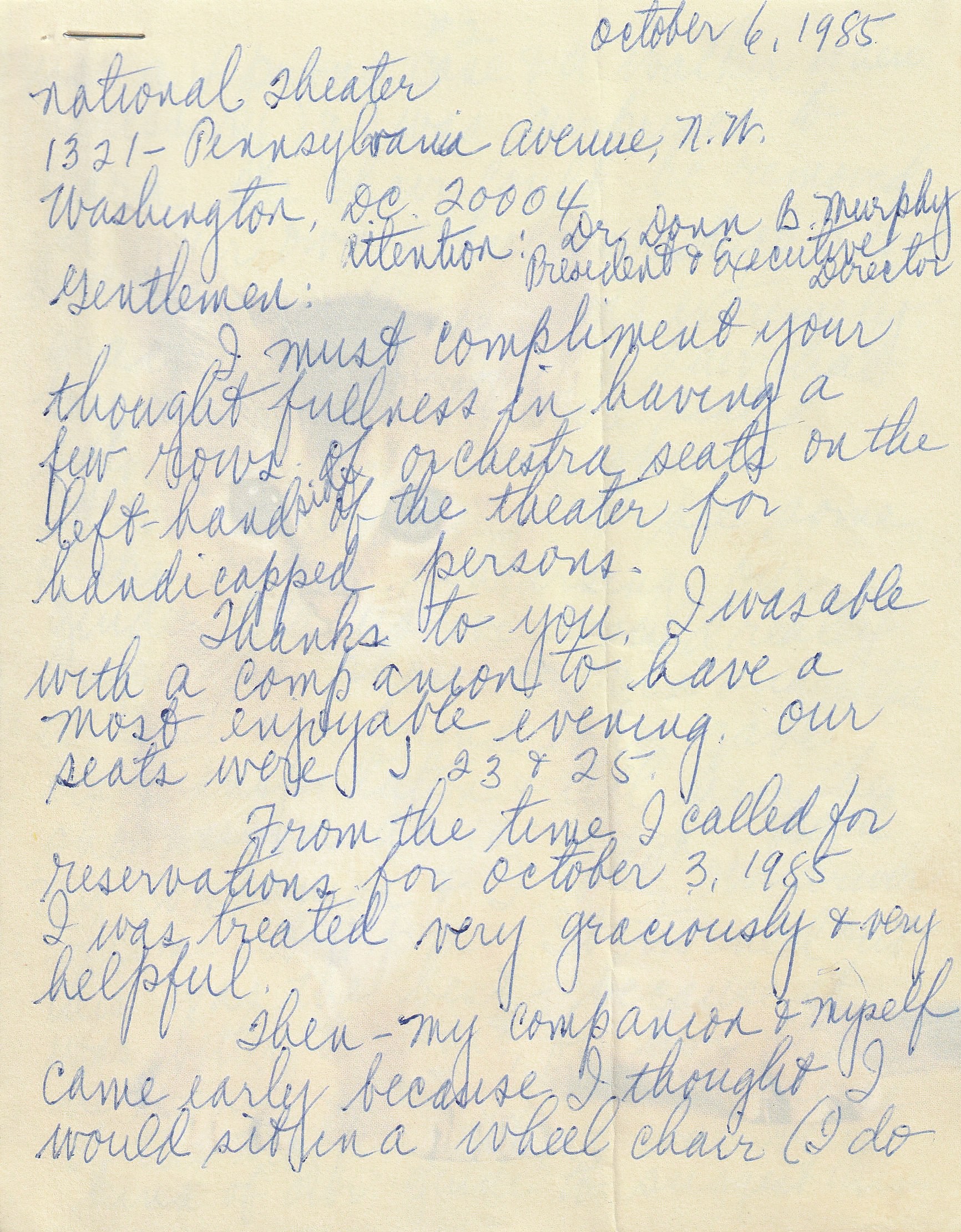

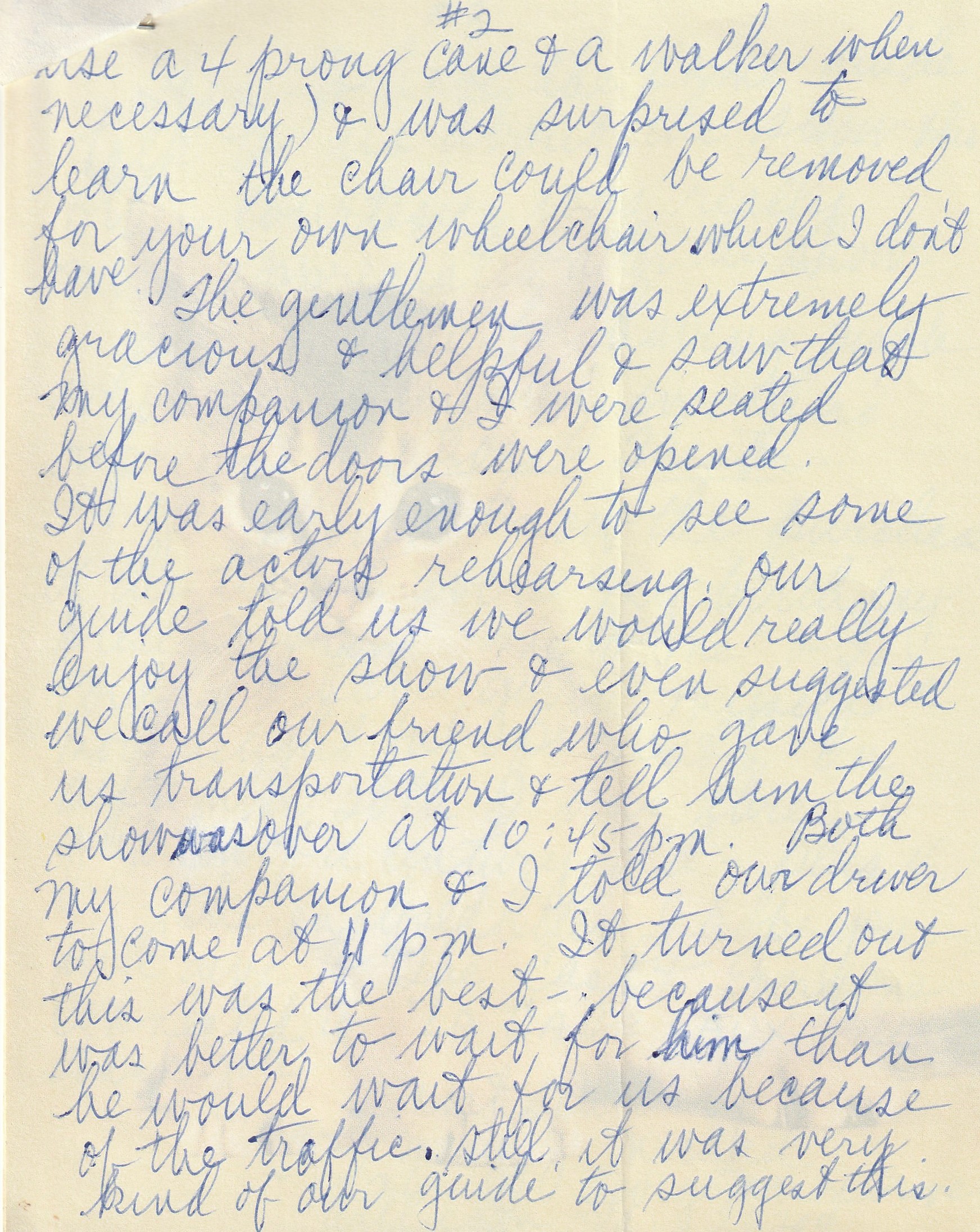

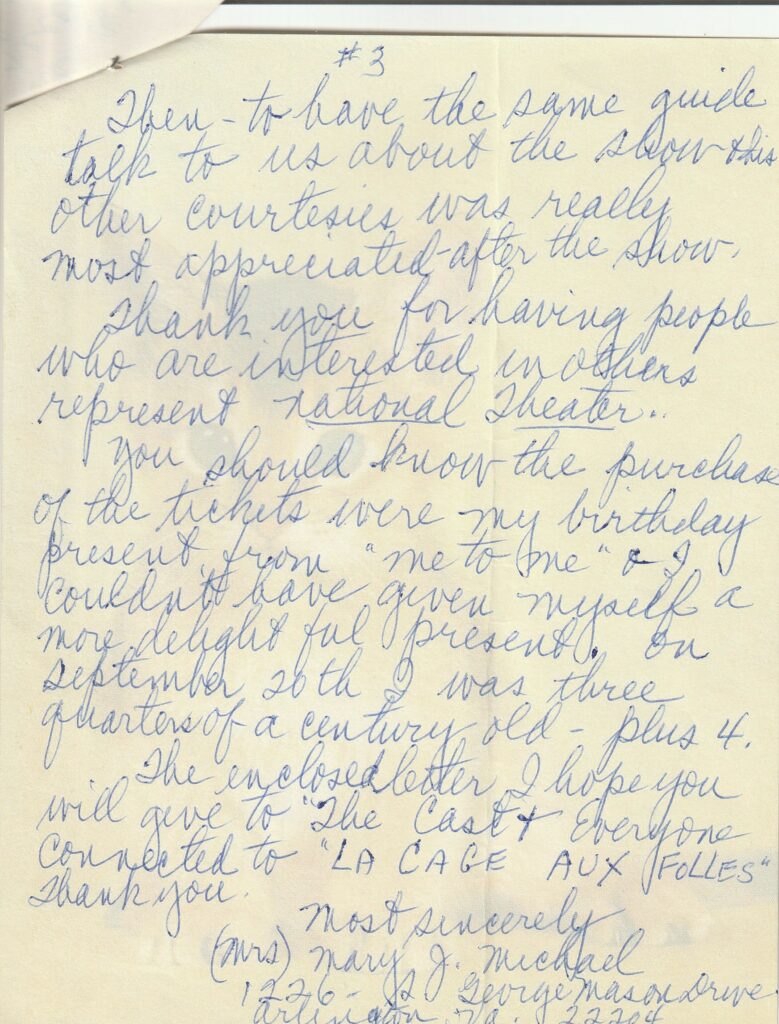

While all the above strategies were critical to creating an accessible theatre experience, it was the consideration and respect of The National’s staff which truly made the theatre feel inclusive for many patrons. There are numerous letters from grateful patrons in the Archive expressing their appreciation of the inclusive attitudes and behavior of the theatre’s staff. One patron wrote in 1985, “Thank you for having people who are interested in others represent National Theatre.” These patrons’ letters highlight how accessibility is fundamentally about respect, and they show how powerful inclusive practices, spaces, and attitudes can be in creating a welcoming and memorable theatre experience.

References:

- Meldon, Perri. “Disability History: The Disability Rights Movement.” United States National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/disabilityhistoryrightsmovement.htm

- Burgdorf, Robert L., Jr. “Fighting for Access to the Arts.” Style Plus. The Washington Post, June 4, 1985.

- “Washington Accessible to the Handicapped.” SunDAY Magazine. Wyoming State Tribune, April 27, 1986.